Imagine if you will, the war in Europe is over. Germany is in ruins. There is little activity except for cleaning up the rubble of war. Most of the clean-up crews are women–known as Trummerfrauen, or “women of the rubble”–as there are few men left following the final blizzard of destruction.

In the last years of the war, 1,000-plane raids over Germany were common, and the B-24 bomber made at Ford’s Willow Run was a mainstay of the force. Ford produced one plane per hour, 24 / 7 around the clock. Bomber losses of ten percent per raid were the norm, which meant that the finest aluminum alloys in the world fell daily from the skies over Germany.

Into this unreal world steps an earnest young German who has spent months recuperating from a land mine explosion. Badly wounded, he was evacuated from Leningrad by railroad flat car just before the Russians broke through. His passion is automobiles, and he is determined, against all odds, to build his own car from the rubble around him.

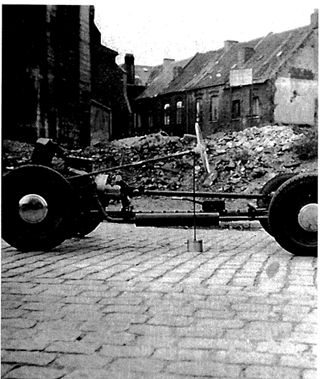

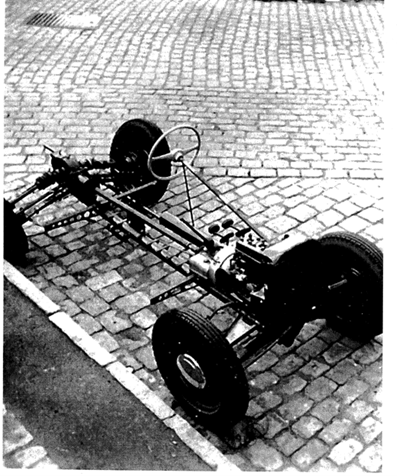

Though he will eventually recieve a degree in Mechanical Engineering, his uncommon intellect and natural feel for the subject will in years to come help produce some of the finest automobiles ever built. The car in his mind now is a two-seater with front mounted engine, rear wheel drive, 4-wheel independent suspension, a “back bone” chassis (years before Lotus claimed it), an alloy body of course, and a two-cylinder motor sourced from a DKW- Lloyd delivery truck. Rear hinged “suicide” doors and styling touches common on 30’s and 40’s cars (rear deck ribbing) complete the picture.

As his wounds healed, the young man named Klaus Arning rested at his parent’s home in Bremen, which was also home to the bombed out Focke-Wulf aircraft factory. Klaus’ father was a Lutheran minister, so the American occupation authorities allowed him sufficient gasoline for travel in Klaus’ car, once it was complete, to visit his congregations. The car had several hidden compartments which were used for smuggling … according to Klaus’ son Ralph.

Klaus spoke good English, was very personable, played a mean accordion and an even meaner piano. He was often recruited to entertain U.S. troops, and in payment received a few cartons of American cigarettes, and/or maybe a bottle of Genuine U.S. Whiskey. In the right hands, this contraband could be bartered for enough food to feed a congregation for days!

I remember Klaus playing piano in small lounge for a few friends in the Las Vegas Hilton during SEMA week. Linda Vaughn, Miss Hurst Shifter, walked by, spied Klaus, walked over and sat in his lap. He continued playing, with a big grin on his face, while his small audience clapped and cheered!

American high-octane gasoline was a Godsend (oops … bad choice, sorry) to the German economy. Shipped by tanker from the U.S., it replaced the low octane, dirty fuel Germany had been making from coal.

The DKW motor needed new pistons, probably as a result of the low-quality fuel, so Klaus simply made new ones. Selecting a suitable alloy from the “gefallene Fruchte” (literally fallen fruit) of wrecked Allied and German aircraft, he cast new pistons by pouring molten aluminum into two holes in the ground. With a foot powered treadle lathe in his parent’s attic, and a whole lottsa smarts, he soon had new pistons and the motor was purring.

Think about all the factors inherent in designing new pistons. First, are rings available? What are the ring clearances required? What skirt clearances are needed as the pistons heat and travel up and down in the bores? What about compression ratio, combustion chamber shape, wrist pin offset, not to mention piston weight and counterweights?

All these hurdles and more were overcome. I’m sure the German authorities gave the car a thorough inspection when Klaus announced, “I made it myself.” and asked for a license and registration. Later earning a degree from Bremen Polytechnic seems almost redundant.

During his stay at the University, a thief stole the precious car and wrecked it in the ensuing police chase.

Regular readers of this column will recognize the name Klaus Arning as the 1960’s head of Ford Advanced Suspension Design, and the mind behind the Mustang I.R.S., the GT-40, several Foyt and Gurney single seaters, and much more. Check the MEDIA section on mustangirs.com for two very well-done articles in RACECAR ENGINEERING, written by Richard Nisley, to whom we are indebted for the pictures of the car. I got to know Klaus researching the “never-made production” Mustang I.R.S. These pictures were taken when Klaus paid a visit to my garage about 1990. He’s trying to explain his design to me, as I try to imagine it installed into an inverted Mustang chassis.

Klaus apparently got to take a GT-40 home once in a while. I wonder if there are any hidden compartments.